This article struck a nerve because of two discussions I had this week regarding OUR museum.

The first was with fellow staff for our upcoming World War I exhibit on whether or not to hang our World War I service flag (or blue star flag). Folks would hang the flag in their window to let others know they had family members serving in the war (see earlier post about service flags HERE). The flag has some wear lines and holes near the bottom, and it was our textile specialist’s concern that hanging for a year or more could risk expanding those holes.

Instead, perhaps we mount the flag on a slant board covered with archival fabric, as we’re doing for another more fragile textile in the exhibit (Marion Billings' Victory Dance dress), BUT, we don’t have a safe place to position a slant board where we need it.

We could photograph the flag and pay to have it reproduced poster size and mounted on foamcore -- and hang that. That would still give us the deep shot of color amidst the army green and dark metal helmets and show a copy of our local flag, not just an image pulled from the Internet.

Or maybe we could buy a repro flag from ebay for not too much money, suggested Meg Baker, our textile specialist, and not worry about light or hands touching it.

Yet, here's the thing: we have the ACTUAL flag that was displayed in a window by a Hatfield family, the Bardwells, representing their sons Homer and Curtis serving in the war. If this flag is not displayed now, for our WWI exhibit, then when? This is it’s time in the sun!

OK, bad metaphor, especially since one side is quite faded from prior light damage -- probably from hanging in the Bardwell’s window. For the record, we have UV-blocking tubes on all our fluorescent lights and no direct sunlight would reach the flag.

These are the sorts of discussions that go on all the time when making museum display decisions -- balancing the value of showing the public authentic artifacts against the responsibility to preserve those artifact for the future.

Here’s what we decided -- at least for now. Hang the real flag on archival fabric for the opening on Memorial Day Weekend and through July 4. But for the remainder of the exhibit, replace it with a poster-sized reproduction on foamcore, noting why we made that decision.

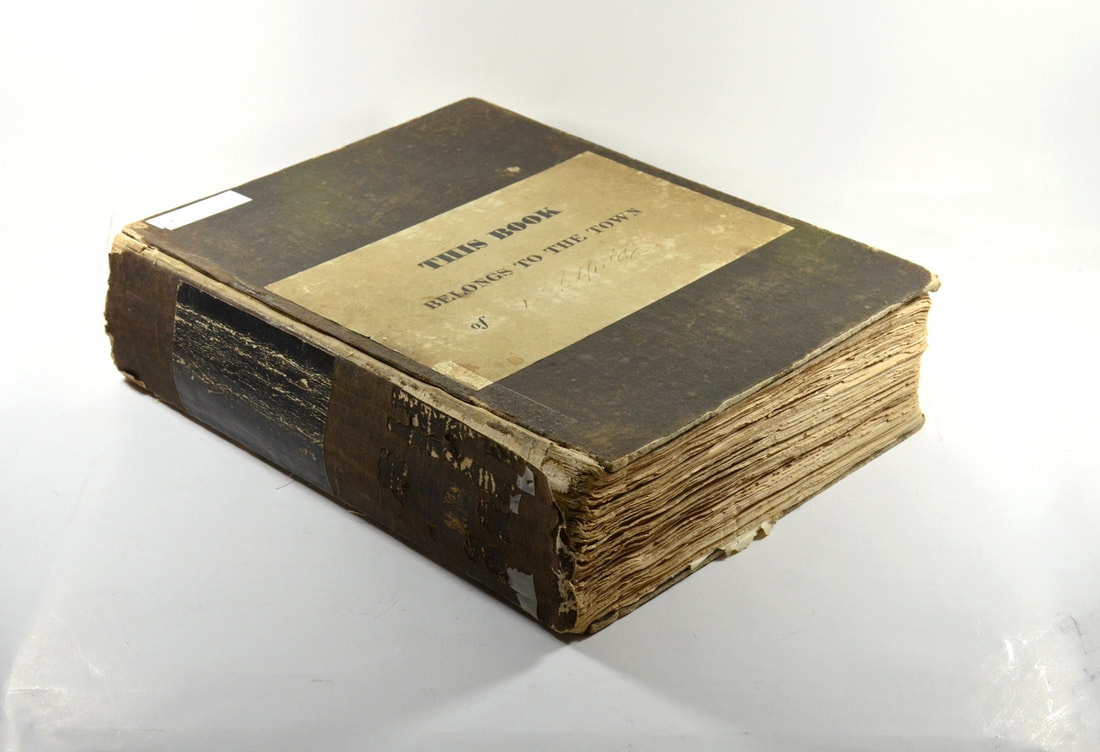

He also asked if he should remove the library pocket and card (with no entries), not on the last page, but 2 pages inside the back cover, especially since the book was marked elsewhere as “Reference, not to be taken out.”

Once confirming the library pocket was not hurting the book or the map, I asked him to leave the library pocket alone, as it helps tell the story of this particular book -- however confusing a story that may be.

Artifacts often mirror life in that way -- confusing and messy. But sometimes their circuitous journeys are also what draw us in.