Amos Newport: the story of a brave man who fled from his owner on a southern plantation under the cover of night to catch the Underground Railroad heading North in pursuit of freedom and a better life. He must have done something special after he was freed in order to be the focus of an editorial written by Robert Romer for the Daily Hampshire Gazette on Jan. 17, 2011, in celebration of Martin Luther King Day. At least that is what I thought when I was asked to read excerpts of that article for this event. It was supposed to be a simple reading – quick and easy. But, when I received a copy of the article, the story that it told was very different from the one that I had expected, and a true display of my ignorance.

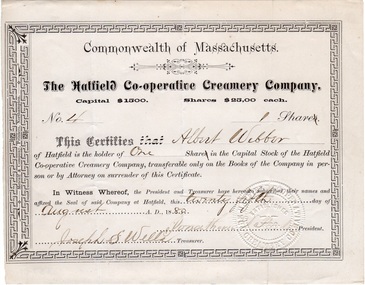

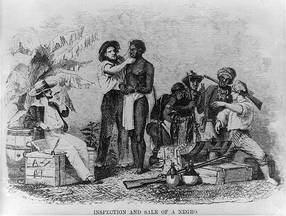

Did you know that in the early 1700s there were slaves working on plantations in Hatfield? Our history books tell us about the early settlers of Hatfield who were farmers drawn by the fertile soil along the banks of the Connecticut River. We have been told about the first and second meeting houses, which were the ancestors of the First Congregational Church we are standing in now. We know about the stockade that was built to protect the first families from Indian attacks. But our town history essentially skips over the fact that there were slaves who worked the land here. Actually, very little is known about the slaves in Hatfield. The only evidence we have comes from tracking the financial records of farm owners documenting the purchase or sales of Negro men, women and children.

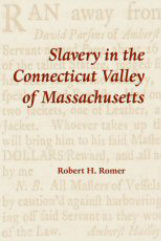

According to Robert Romer, author of the book Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts, Amos Newport was born in Africa around 1715. He was captured as a boy and taken to America on a slave ship, eventually arriving in Springfield as the property of David Ingersoll. Ingersoll then sold him in 1729 to Joseph Billing of Hatfield. At that time, he would have been 14 years old. “Very little is known about Amos’s life in Hatfield,” says Romer, “except for the very important fact that in 1766, Amos decided that he did not want to be a slave any longer and went to court to sue for his freedom.” He would have been around 51 years old.

Romer’s article reports that there were a number of “freedom suits” by Massachusetts slaves around this time, and many of them were successful because the slave could produce evidence that a previous owner had promised his or her freedom. “But Amos made no such claim – he simply wanted to be free. Billing produced a bill of sale, properly executed and witnessed in 1729,” says Romer, which read, in part, “ ‘I David Ingersoll… have sold & delivered a certain young Negro Boy… for consideration of fifty pounds to Joseph Billing of Hatfield…’. The jury had no choice but to conclude that Amos was indeed a slave belonging to Joseph Billing.” Romer reports that Amos appealed the decision to the highest court in the province, but unfortunately, the Superior Court simply confirmed the decision of the lower court.

“Even though Amos never did become free,” says Romer, “he tried, through every legal means available to him, and even the act of filing those two court cases probably contributed in some small way to the gradual ending of slavery in this state during the last two decades of the 1700s.” Romer goes on to tell us that Amos’s son did gain freedom and the Newport family became important to the fabric of the local community. Amos’s son and grandson were founding members of Hope Church on Gaylord Street in Amherst, which was originally an all-black church dedicated in 1912.

Slavery in Massachusetts

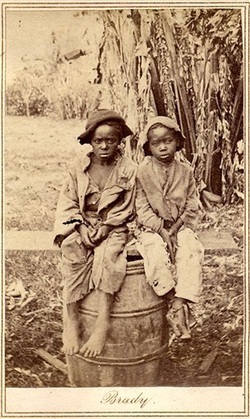

Reading Mr. Romer’s article caused me to wonder about slavery in Massachusetts. During a search of the Internet, including Douglas Harper’s “Slavery in the North” website, I discovered that Massachusetts was the first slave-holding colony in New England. Slavery is said to have predated the settlement of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Samuel Maverick, apparently New England’s first slaveholder, arrived in Massachusetts in 1624 and owned two Negroes. However, the first certain historical reference to African slavery is in connection with the Pequot War in 1637. Of the few Indians who escaped slaughter during that conflict, the women and children were enslaved in New England. But most of the men and boys, deemed too dangerous to keep in the colony, were transported to the West Indies and exchanged for salt, cotton, tobacco and black slaves.

Massachusetts merchant ships were supplying slaves to Connecticut by 1680 and to Rhode Island by 1696. The expansion of New England industries in the early 1700s created a shortage of labor, which slaves filled. From fewer than 200 slaves in 1676, and 550 in 1708, the Massachusetts slave population jumped to about 2000 just seven years later in 1715.

Although Massachusetts, like many American colonies, had roots in scrupulous fundamentalist Protestantism, this was not a barrier to slave ownership. The Puritans regarded themselves as God’s Elect. Their Calvinist doctrine of predestination supported the Puritan belief that blacks were a people cursed and condemned by God to serve whites. Cotton Mather told blacks that they were the “miserable children of Adam and Noah,” for whom slavery had been ordained as a punishment.

The story of Amos Newport is not the story of a slave from the South. It is the story of a man who dreamed of freedom as he plowed the fields that we now call home. Historical accounts of slavery in Hatfield are meager because slaves were considered property. They were valued only for their ability to get work done. Amos Newport’s story is a part of our history. It is our responsibility as parents, mentors and human beings to recognize the atrocities that have been committed in the past, fight to resolve similar situations of human trafficking in our present, and take action to ensure that our children and our children’s children treat the people of the world with respect and dignity. We are all God’s people.